Why Schools with the Most Funding Have the Most Problems

As the first period bell rings at Franklin High School, students run through the halls and in and out of bathrooms. Littering and cursing, they pay no mind to their tardy attendance record. While security and teachers on hall duty would alleviate this issue, the gross understaffing of the building makes this impossible. For Kelly Boyd, a teacher at Franklin High School in Baltimore County, Maryland, this is her daily reality. “When students don’t see the presence of teachers on hall duty (because they are pulled for class coverages), when students don’t see consistent security presence in the hallways (because we don’t have a full-time security officer), and when the grounds and facilities aren’t kept as clean as they could be (because building service is consistently understaffed), it affects the way students see their school as being ‘good’ or ‘bad’,” Boyd says. If Franklin had more funds to pay a larger staff, perhaps the idea that students were getting an education in one of the “better” Baltimore County schools would be more believable.

However, Franklin High School and its parent, the Baltimore County Public School system, are not underfunded. It ranks in the top half of all Maryland schools for total funding per student, and yet is ranked 20th of the 24 county districts, according to School Digger (a website that ranks school districts based on test scores). Boyd suggests this may be due to a poor allocation of funds given to the district. “One of the biggest ways that funding impacts the quality of education at Franklin isn’t in the classroom, but in the areas outside of the classroom. We’ve received many interesting bits of classroom technology in the 8 years that I’ve worked here (students have 1-1 laptops, all classrooms have document cameras and projectors, etc), but in terms of the hallways, bathrooms, and in-between class activities workings, I can see the ways that financial struggles can take a toll.”

Delaney Maul, a 9th grader at Franklin, has seen similar patterns. “The quality of bathrooms and many of the textbooks are in really bad condition, the bathrooms are disgusting,” she says.

It is a common misconception that schools with more problems are schools with less funding and little attention from higher-ups in public education. Counties that are populated with more minority students often seem less resourced and therefore have less fortunate public school options. “Per Pupil” is a figure represented in Maryland Finances and Demographic Information that measures the total funds distributed for one individual student in the county. The funds for this singular student, as well as the school district as a whole, are broken up into local, state and federal allowances. In the case of Maryland public schools, when local funding is particularly low, the state and federal budgets increase accordingly. The maps below depict the differences in local funding and state funding.

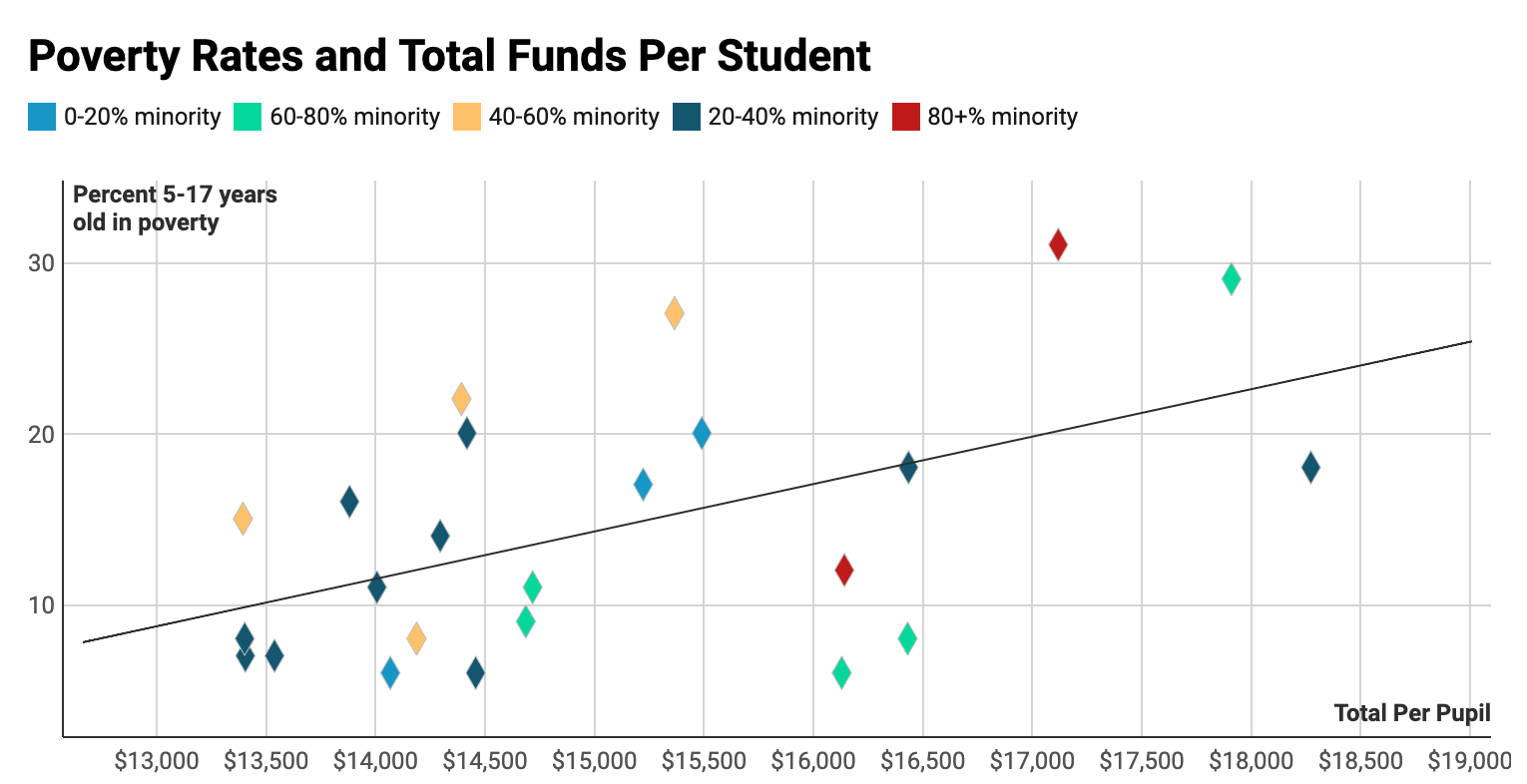

In most cases, the counties with lower local per pupil funding, have higher state per pupil funding. Take Worcester County for example- it has the lowest state funding and the highest local funding. Ideally, this would create equal opportunities between wealthier counties with more resources and impoverished counties with fewer resources. When the local, state and federal per pupil funds of each Maryland county are combined and compared to the percent minority of every county, it is clear that some of the most racially diverse areas receive more money (the correlation between minority percentages and total per student funding is nearly 42%).

But funding isn’t the only dimension of resources faced by school districts. And yet, attention is often given to this dimension over other, more crucial resources. Boyd is quoted with saying the following points: “What sometimes concerns me is the way those funds end up being allocated. When they are tied to test scores and graduation rates, we often see schools teaching to the test in order to try and obtain more funding for at-risk students. Such practices can shift the focus from what students need to what teachers need, and can contribute to student disengagement, which contributes to a really awful feedback cycle of students hating school.”

When ranks and funds are given to schools based solely on test performance, it skews the focus of education. Students from wealthier neighborhoods grow up with more resources and different support systems outside of school, which affects their educational development. While investing in resources that center around curriculum helps school systems rank well, it does not help students with individualized learning needs (work ethic, patience, diligence, etc.). Diana Spencer, Communications Officer for Baltimore County Schools, said the following of education and poverty levels as it relates to inequity: “We have succeeded in closing the graduation rate gap between black and white students, but not the achievement gap. The reasons for this are so many – from the multigenerational challenges of being black and brown in this nation (from redlining to the inequities in the justice system), to unconscious bias on the part of teachers (most of whom are young white women), to inequities in health care and early childhood education. Because of the intergenerational poverty and disinvestment in the neighborhoods of Baltimore City, that school system is failing by every measure. We are not. But we, like every other public school system, has a long way to go in achieving equity and helping every student fulfill his or her promise.”

Funds don’t alleviate deeper systemic issues. A laptop does not teach a child to learn, and neither does a standardized test. As school districts continue to push toward standardized education as a method to seize funding, they will inherently lose their ability to encourage creativity and excitement about learning. While it is important to offer programs like free or reduced-price lunch, this doesn’t fix the systemic issue- it’s a temporary patch on a leak that is easier than replacing the pipe entirely.

Obviously, we should fund schools equally. But how that funding is used must be considered using more factors than test scores. Students in impoverished neighborhoods have different developmental needs than students growing up in wealthier neighborhoods. Experiences they are surrounded by, opportunities they have available outside of school, and general encouragement to think, learn, and grow inside and outside the classroom differ. While the funds are available, these factors may not be considered in the allocation process of these funds appropriately. Attention not only to test scores and quantitative measures of performance, but qualitative factors in students’ environments is necessary to achieve substantial effective education reform.