Metropolitan Police Stop and Frisk: Unsuccessful?

A 10-year-old black child was taken from the sidewalk and handcuffed into police custody earlier this month in Washington, D.C.

This followed a report that three boys robbed a young man of his wallet in the district’s northeast quadrant. The Metropolitan Police Department positively identified the 10-year-old boy with description of one of the attackers, which lead them to stop and detain him.

Videos of the incident gained over two million views on Twitter prompting retweets and comments about his calm and compliant demeanor and the lack of reason from the police officers.

🚨 Police falsely arrested a 10 year old and put him in handcuffs : Washington, D.C.'s attorney general says he is "totally innocent" and will not be charged. Now he has nightmares and can’t sleep pic.twitter.com/Ng2ItgWwYj

— GG 🧚🏽♂️💫🍑 (@ggqt3) April 10, 2019

Later, D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine said the boy was “totally innocent” after reviewing surveillance footage. Chaquitta Williams, the boy’s mother, shared with the media that the boy was suffering from harmful psychological effects following his stop and detainment.

The Fourth Amendment defends the Americans’ right to be secure in their persons and houses without searches, seizures or arbitrary arrests.

Stop and frisk is defined by the Cornell Legal Information Institute as a “brief, non-intrusive police stop of a suspect.”

While the average age of D.C. citizens stopped in 2018 was 30 years old, 748 juveniles were stopped: 663 were black, and 57 were white, based on Metropolitan Police Department data. This means that 93% of children under 18 who are stopped by police are minorities.

Davone King, 19, was a juvenile in 2016 when he had his first interaction with the police. King walking home from Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering High School in northeast D.C. when eight police officers in bulletproof vests jumped out of unmarked cars and told him not to move.

“They all got their hands on their guns already,” King recounted. “Like if I run, do I really want to get shot in the back?”

King and his three friends were searched in their school uniforms and never told why.

“No one wrote anything down, they just came up and searched everybody…said they’re checking for guns,” King said. “You’re not supposed to be able to do that.”

“Reasonable suspicion for a stop does not automatically provide the basis for a pat down,” according to a prepared statement by the Metropolitan Police Department’s Press Office. “[A] set of facts, circumstances, or reliable information that would lead a reasonable and prudent police officer to believe that a crime has been committed, or is about to be committed, and that a certain person committed it.”

In an interview on Monday, King said “if you like the police, something is wrong with you.”

DC Councilmember Brianne Nadeau wrote an essay for the Washington Post in February that focused on her frustration with the lack of connection between community policing and community safety in Ward 1 as a result of stop and frisk.

Michael Abate, 20, never questioned the authority of police growing up in suburban Maryland. He was raised to recognize a connection between police officers and safety. When he came to the district to attend college, however, he had his first negative encounters with law enforcement. “While I was riding in my friend’s car, Metropolitan Police stopped [us] for relatively no reason,” said Abate. “Obviously when it’s a car full of black men, we’re kind of f***ed in the situation.”

The DC Office of Police Complaints data shows that 89% of reported uses of force by MPD officers in 2017 involved black subjects; the most common officer-subject pairing was white officers using force on black subjects, which accounted for 44% of all reported uses of force.

In 2017, a 40-year-old black and southeast D.C. resident, M.B. Cottingham, was subjected to a forceful patdown by Metropolitan Police. WAMU shared a quote from Cottingham:

“If I didn’t have the video, no one would believe me,” he says. “The video speaks for itself. It shows the truth … the video shows everything I say was the truth.”

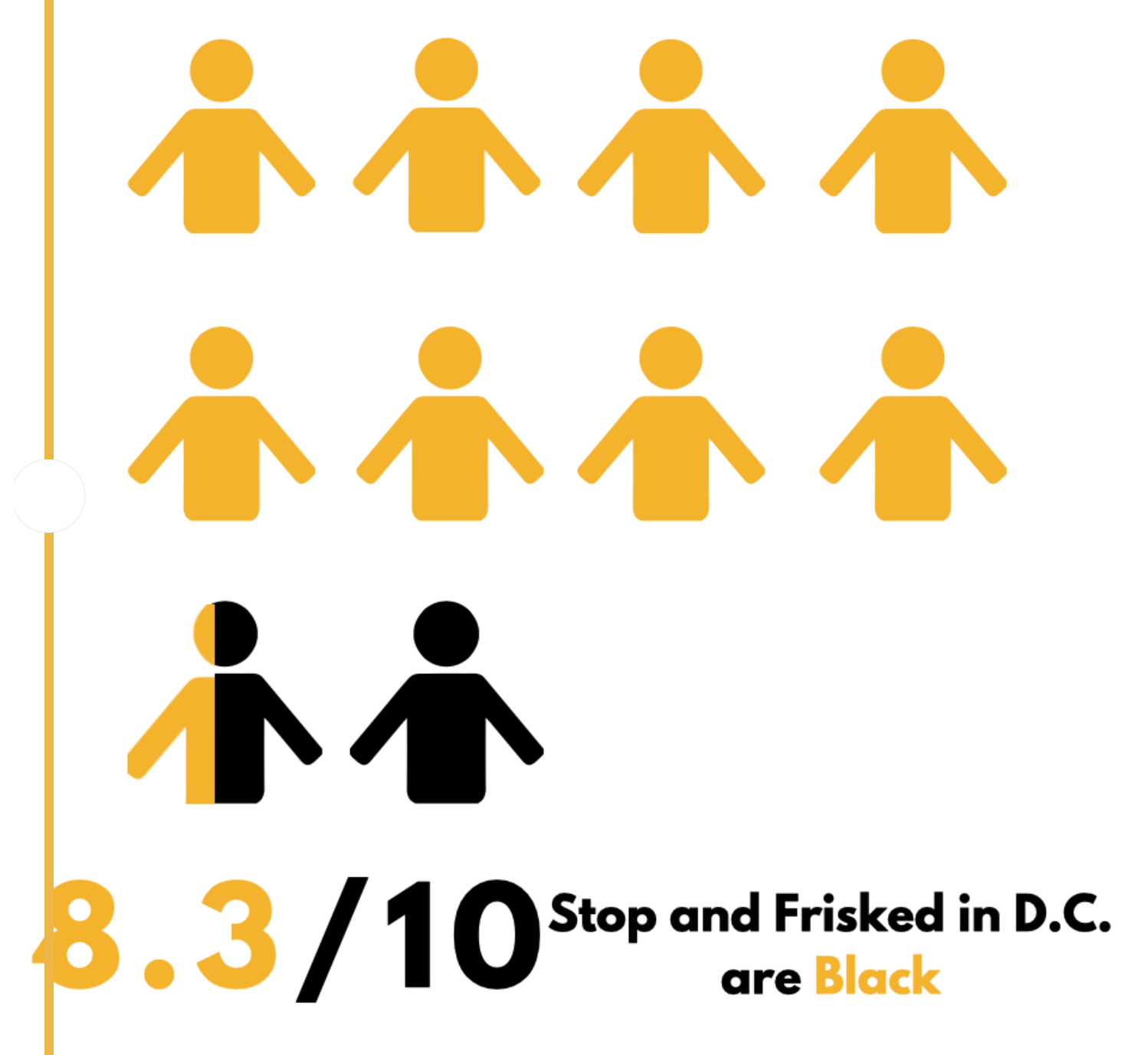

Regardless of whether force was used in a search, 83% of stop-and-frisks were of black residents, who make up 47% of the DC population

Washington is not the only city that disproportionately conducts random searches on black populations.

According to maps analyzing police stop data, the three regions in D.C. with highest recorded stops of black citizens occur in census tracts 44, 58 and 73.

Tract 44 surrounds the U Street Metro Station and the area near Howard University, a historically black university in D.C. According to Census Reporter, the population in that area is 67% white. Tract 58 covers the area between Lafayette Square and Chinatown, which Census Reporter shows as 61% white. Tract 73 is near the Congress Heights Metro Station in southeast D.C. and is demographically 91% black.

The Neighborhood Engagement Achieves Results (NEAR) Act was implemented by the D.C. Council in 2016 to train police to be unbiased. Mayor Muriel Bowser fully funded all 20 provisions of the NEAR Act when it was implemented. In 2017, she wrote a letter to the DC Council Chairman in which she said $300,000 should be added to the MPD budget for NEAR Act implementation and data collection funding.

Based on the high quantity of stop and frisks in suspicious circumstances, in an effort to prevent crimes, the rate of violent crimes should be decreasing.

However, there has been an overall increase in homicides since 2016 when the act to lessen police bias was put into place. The right people are being patted down. Perhaps the funding will be redirected in the future to specifically train Metropolitan Police Department units in areas where the stop counts are not racially disproportionate.