District Sees Number of Cyclists collisions Rise

On June 23 Malik Habib was out at night, biking around the city to deliver food like the countless other teenagers in the district. Only on that night Habib never made home after his bike caught on a street car rail causing him to move forward onto the path of an incoming charter bus. Habib was rushed to the hospital but died of his injuries.

While in the past most fatal cyclist accidents are quickly forgotten, this time it was different. In the weeks and months following Habib’s death hundreds of bikers protested in the city by blocking roads and marching on city hall. Colin Browne, who works for the Washington Area Bikers Association (WABA), an advocacy group that helped organize the protests, believes the outrage should not have surprised officials.

“While we don’t want to blame one department many cyclists in the city have felt for a long time that the city government and DDOT are not doing enough to protect them,” Browne said.

As public transportation use has declined, multiple city governments across the country have been struggling to find ways to protect pedestrians and bicyclists. With biking becoming an increasingly popular activity in the U.S., especially for young professionals getting to work, the need to protect bikers has grown as injury and fatality rates increase.

In the district biking has become more prominent in the city over the last ten years with a number of bike clubs and bike sharing programs being formed. Browne says, the popular Capital Bikeshare, founded in 2010, has provided a “low cost barrier” to getting into biking as customers can rent bikes for only a few dollars.

The recent surge in biking can also be attributed to the district’s expanding young professional population which Derek Hyra, an American University professor on Urban politics, has studied over the past decade.

“Unlike in other cities during the great recession, D.C. saw an increase in its populations with most newcomers being millennials looking for work,” Hyra said. So, with biking becoming a larger part of the city’s transportation system, advocates like Browne say the district should try and emulate other cities that are more welcoming to bikers.

“Portland would be a great place to be in terms of allowing safe biking conditions on the road but honestly we would really like to see strides made to bring D.C. closer to Europe,” Browne said.

But in 2015 that’s exactly what the Bowser administration promised when they announced the Vision-Zero Initiative Based off a policy used in Sweden, the plan wants to see all traffic injuries and deaths to reach zero by 2024. It will do this by increasing the fines placed on reckless driving, for instance a failure to yield to a pedestrian would cost a driver $200 instead of $50.

Yet almost five years after it was announced Vision-Zero has not stopped the demands for better protection for bikers in the district. In fact, despite the goal of no zero injuries or deaths by 2024, traffic collisions involving bikes have increased over the past 10 years.

In 2018, the numbers of bikers injured on the streets of Washington peaked at 630 riders, according to data from the District Department of Transportation (DDOT). It appears not even the change in fines brought on by the Vision-Zero Initiative was enough to decrease the number of biker accidents.

For those involved in the districts biking community, like Browne, these numbers are not a surprise.

“We see vision zero as not really being a bike thing and more as a directive to encourage safer driving in the city,” Browne said.

However, Terry Owens, the Public Information Officer for DDOT, is adamant that the Vision-Zero Initiative should continue and will protect bikers.

Owens says that the Mayor’s announcement in 2015 and the increase to traffic fines were just the initial steps of the policy. In 2018 further plans attached to the initiative, include installing new left turn infrastructure on intersections to prevent cars cutting across lanes.

While Browne sees the plan right now doing little to changing the actual infrastructure of the city, he does note that if it were changed to be more accommodating to bikers than fatalities and injuries would begin to lower.

Transforming infrastructure has been suggested, by other cities, as a way to curb pedestrian and biker collisions with cars. Prioritizing which Wards to alter first may be key to bringing down the numbers as three Wards in the district, currently account for over 70-percent of all collisions.

It was in Ward Six, the third highest bicycle collision rate in the city, where Habib was struck by the charter bus.

However, since these policies are now just being implemented the city will not know for a few years if they will work. However, looking at Seattle, which adopted traffic infrastructure projects to accommodate their bikers earlier than the district, could provide the answer.

Bicycling Magazine voted Seattle in 2018 as the best bike city in America. The magazine cited the city’s construction of concrete barriers between roads and bike lanes as well as rail sections for bikers to lean on while they were stopped as innovative ways to protect bikers.

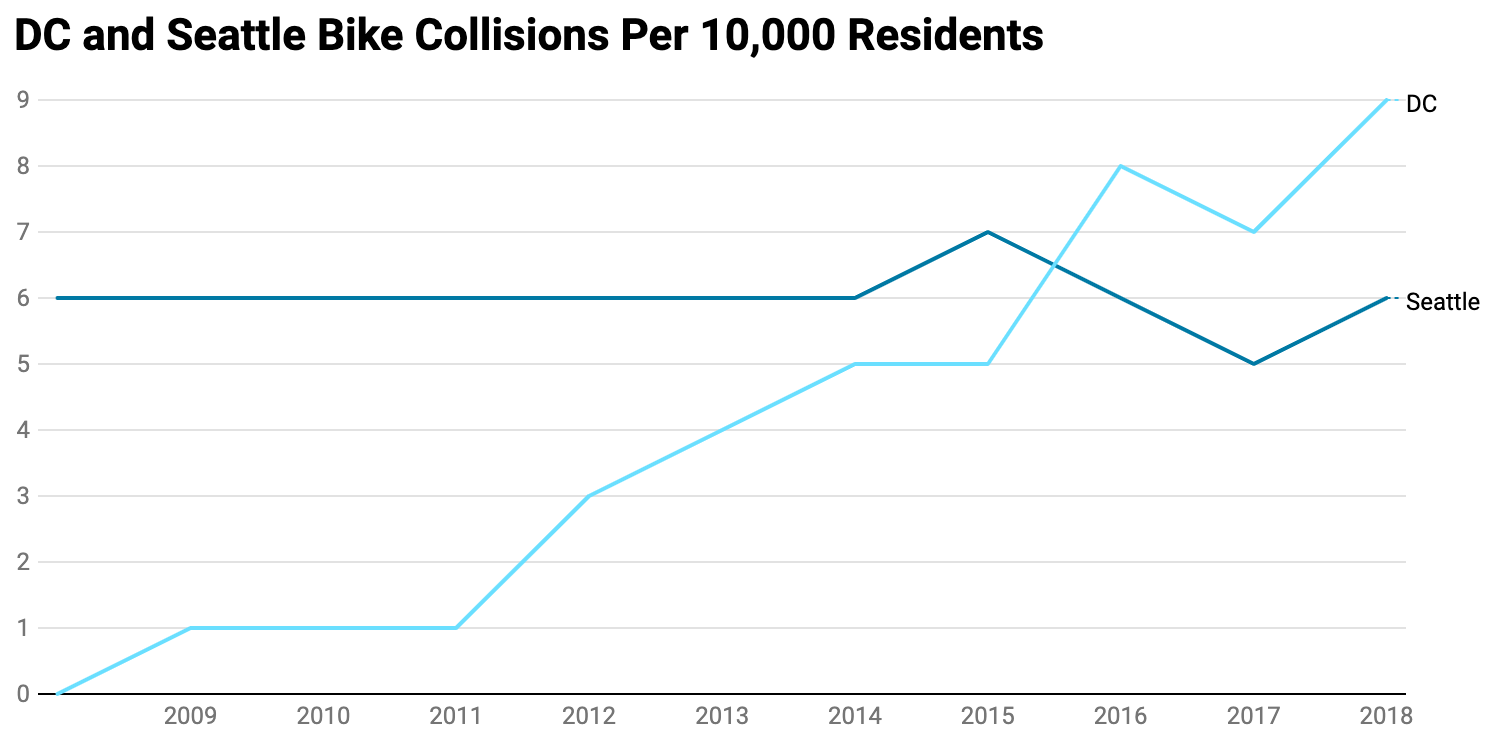

Looking at the data for bicycle collisions, provided by both cities’ department of transportation, shows that infrastructure created in Seattle over the past 5 years has made a difference.

By 2018 8 per 10,000 district residents were involved in a bicycle collision versus only 6 residents in Seattle. This is even more striking given Seattle has about 30,000 more citizens than the district.

Yet despite Seattle’s ambitious infrastructure projects, even they have not reached zero fatalities with two bikers killed in 2018.

As the Vision-Zero Initiative begins to be implemented, officials may want to scale back the zero fatality and injury number by 2024. However, looking at Seattle, were similar efforts to change the infrastructure done in the district then it may finally begin to reverse the trend of bicycle crashes.