For AU basketball, the Princeton offense may be their root of inefficiency

Mike Brennan’s unfolded arms dropped down to his waist and carried with them the weight of frustration.

With just seconds remaining, American blew a shot to take the lead with a wide-open three from the corner.

“We had a couple shots down the stretch where you have to make them to win a game like this,” Brennan said after the contest, “and we didn’t.”

American University’s 64-58 defeat to Wagner is just one of the program’s 83 losses in the five seasons since it last made the NCAA tournament in 2014. Head coach Brennan was in just his first year at the helm of the program, yet coached his team to an appearance in the second round of the tournament and a Patriot League championship. Brennan, a former Princeton University basketball player, installed his alma mater’s offense into AU’s everyday gameplan. Fans and media considered his offense one of American’s most important additions.

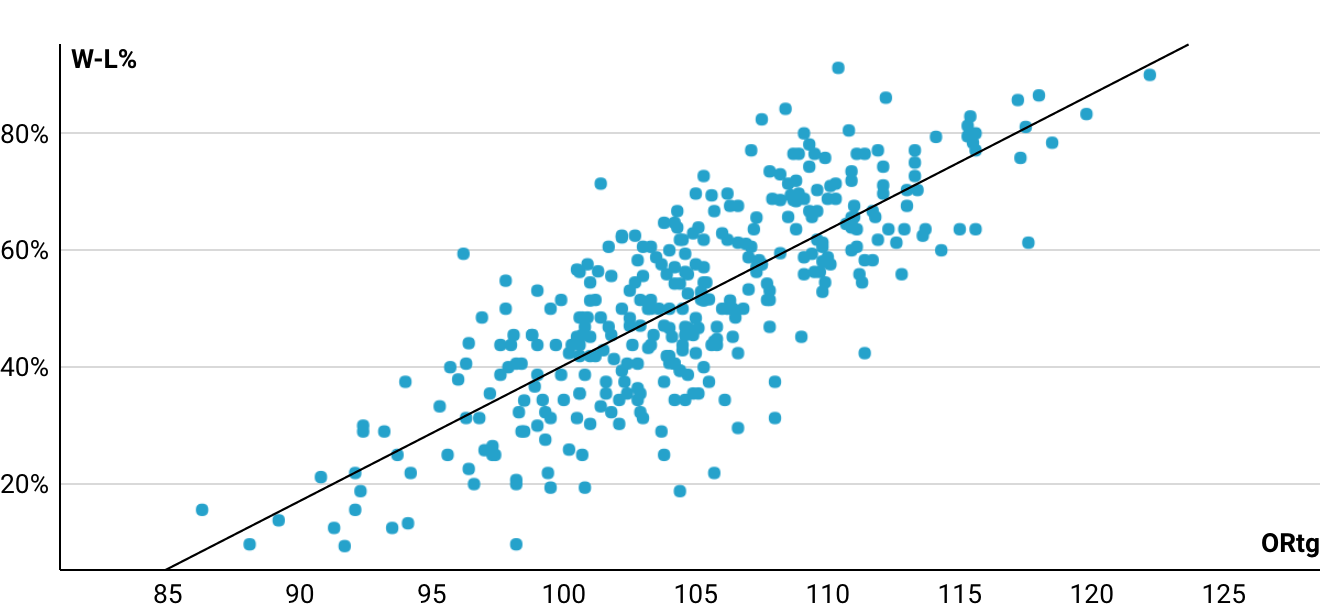

But with little success in the years since, one has to wonder what’s gone wrong on the court. Is AU’s Princeton style attack actually effective, or has it held the team back? Analytics, as acquired by Sports Reference, suggest American has been ill-equipped to run the offense for years – exposing a major inefficiency in their gameplan.

In fact, in the 2017-18 season the Eagles were ranked just 325th out of 351 programs in terms of offensive rating. This statistic rates how efficient a team is at producing points for its offense, meaning that AU ranks among the lowest schools in the country at scoring efficient buckets. That year, the team won just six of its 34 games, finishing the season with the 338th best win-loss percentage in the country.

Obviously, ranking among the bottom-tier in terms of offensive rating is bad for AU basketball. But it is especially worse for a program whose offense is fundamentally designed to slow down the game and find the most efficient shot possible.

Pioneered by coach Pete Carrill at Princeton, and discipled by Mike Brennan, the strategy relies on constantly moving the ball between teammates. According to Dr. Jim Gels, a coach of more than 30 years who also provides resources and information to young coaches, the Princeton is highly complicated. It requires all five players on the court to be skilled at dribbling, passing and outside shooting. When asked about the offense’s basic requirements, Gels referred to his teachings on his consultation site, Coach’s Clipboard.

‘“They must possess some ‘basketball sense’ or IQ in order to read the actions of teammates and of the defense,” Dr. Gels wrote. “The offense breaks down into a series of 3-man plays, with some 1-on-1 play also possible.”

Scott Greenman, an assistant coach at American, is no stranger to the offense. Having coached at Princeton himself, Greenman has spent the last 12 years practicing many of the same principles as he learned at Princeton, though not necessarily the same actions.

“Some ‘Princeton Offenses’ probably run more ‘set plays’ than we do and may focus more on the actions than the teaching points or concepts,” he said. “We believe in running an offense that involves everyone, makes everyone better, and gives our team the best chance to win. We focus a lot on playing unselfishly and working together to get the best shot possible each time down the court.”

In an email, Dr. Gels said that when it is run efficiently the Princeton holds many benefits. Players are always trying to help each other get open, he said. Since the offense relies on outside shooting, having a capable center who can step away from the paint and shoot effectively is a major bonus of the system. In doing that, the offense stretches the floor and imposes a real challenge on opposing defenses.

In the 2013-14 season, Brennan’s AU Eagles demonstrated how successful the Princeton can be, given the right players. Comparatively, American made a greater percentage of three-point shots on average than the average of each school in the NCAA. In the Patriot League alone, AU ranked first of all teams in average three-point field goal percentage, converting 40.1 percent of their shots. In terms of total average field goal percentage, AU ranked as high as eighth in the country.

So, why hasn’t that success carried over to today?

For all its benefits, the Princeton also has its challenges. According to Greenman, the offense isn’t the easiest to teach players because it requires players who have developed advanced skill sets. Teaching players how to make good decisions on the court, he said, takes a lot of time.

“It’s not nearly as complicated as it’s made out to be – it just requires a good feel for the game,” Greenman said. “Like any offense, it takes a little while to learn and feel comfortable in, but I don’t think there’s much more of a learning curve for the Princeton offense than most offenses in college. Every offense takes a little while to learn or master, and the more you know how to play, the easier it is.”

Dr. Gels, however, disagrees. According to him, the offense is often too complicated for younger players.

“First, you usually won’t have five really skilled, interchangeable players at that age, and they won’t have the basketball IQ yet,” he said. “Younger players aren’t ready to be shooting up 3-pointers.”

This is especially problematic for teams that shoot poorly from the perimeter. In the 2017-18 season, AU ranked 242nd in three-point field goal percentage. The Princeton is a bad system for teams that struggle from three-point range, according to Dr. Gels. Instead, they should shift to an offense that “revolves around the post players” rather than their guards.

Offensive stagnation, bad shots and turnovers are the three biggest indicators the offense is at a stand-still, he said. The most helpful metric for evaluating performance, however, is player efficiency rating (PER). This metric attempts to summarize any given player’s contributions on the court in one number. In other words, it is a rating of their overall statistical performance.

Per AU men’s basketball’s advanced metrics, as collected by Sports Reference, the program’s average PER has steadily declined in most years since the success of the 2013-14 season. This means that on average AU basketball players have played less efficiently over time, though this is not true for all players. Star point-guard Sa’eed Nelson, for example, has increased his PER in each of his three seasons at AU.

Although the average player has become increasingly inefficient over time, both Dr. Gels and Coach Greenman suggest that young players can grow into the Princeton system. “Essentially, just like any offense, having an older team with experience makes a world of difference,” Greenman said.

As they develop, they may adapt and become more efficient players, as Sa’eed Nelson has done over time. But as a program overall, AU’s inefficiency has only become more apparent. Their offense is stagnant, they shoot poorly from outside and they play inefficiently.

But should AU really overhaul the way they coach their offense? Maybe not, but it is one of several remaining options for the program. Yes, AU can replace the Princeton and start recruiting and coaching players who fit a system more tailored to their talents. They could double-down on the Princeton and gamble on their young players growing into the gameplan. Or, using the data to their benefit, the team can focus on eliminating the areas of their game that are the least efficient. They can improve as shooters, passers and dribblers. Coaching staff can draw up new ways to expose defenses with a good look at a good shot.

According to Greenman, AU already reviews a “good amount” of analytical data, though he was reluctant to give away any secrets. On top of analytics, the coaching staff pays close attention to practices, where they watch for effort and attention to detail. Numbers, after all, only really paint half the picture.

The data isn’t all bad for American, but until they do something about, it may only get worse.